The Complete Guide to Writing a Report for a Scientific Experiment

Fatima Perwaiz and Sabieh Anwar

A common misconception among many students is that by opting for humanities, one is spared of mathematics and by choosing sciences, one is freed from the need to write. While the former might be true in some rare instances, the latter is an absolute myth. From writing research papers, experimental reports, grants, and research proposals to authoring books, scientists encounter several instances where they need to execute profound and convincing writing skills.

All forms of technical writing are equally significant, but this article categorically emphasizes the skills and techniques required for writing a comprehensive experimental lab report. Since several tips discussed in the guide come from the personal experience of experimental physicists, there is room for adaptation and exercising personal choices.

What is an experimental lab report?

Several undergraduate and graduate courses in pure sciences and engineering programs include laboratory sessions to provide students with hands-on practice. Experiments, with a time-span from a few days to a couple of semesters, usually require a detailed and insightful report at the end to elucidate the theory, spell out results, and discuss the lessons learnt from the investigation. So, the first thing to understand is that what is a lab report?

A lab report is fundamentally your account of the experiment you have performed. It is presented in an organized and easy-to-discern manner.

This definition might seem generic, but it has some essential points that have been marked bold.

First, as all the students who perform the experiments in the laboratory are unique individuals, their reports are likely to be different. It doesn’t mean that science depends on the practitioners’ mood, attitude, or the color of their clothes and that the outcome would change depending on who’s performing it. Instead, it signifies that every individual possesses a different approach and can present different account of the experiment.

Yes, it is recommended to follow a prototype structure in your report to maintain coherence, but depending on your experiment and data, and your personal choice, you can bring variation to the structure and presentation of the report.

Second, as a report is essentially a way of sharing your research with those interested in the field, it is important for it to be easily comprehensible. If this is not the case, your efforts might go in vain. In this article, we will discuss several such ways to improve your report writing skills.

What are the prerequisites for a well-articulated lab report?

If you think that performing the experiment is the only requirement to write an extensive and insightful report, you are mistaken. There are some prerequisites to writing the report that you should never overlook.

1. A well-maintained lab notebook

The first and the foremost step in becoming a competent and skilled experimentalist is to almost religiously maintain a lab notebook. Depending on how long and complicated the experiment is, you should obtain a notebook with enough pages. Making notes on random pages that you slipped into a book or pile in a drawer is a common mistake. Later, not being able to find those loose papers while writing the report could be the most frustrating part of the experiment.

People who are not fond of the conventional form of journaling can also opt for digital options available. Some apps and websites offer interactive and convenient GUI for experimental journaling. The Physlab has developed a web-based solution called PhysDiary for the purpose.

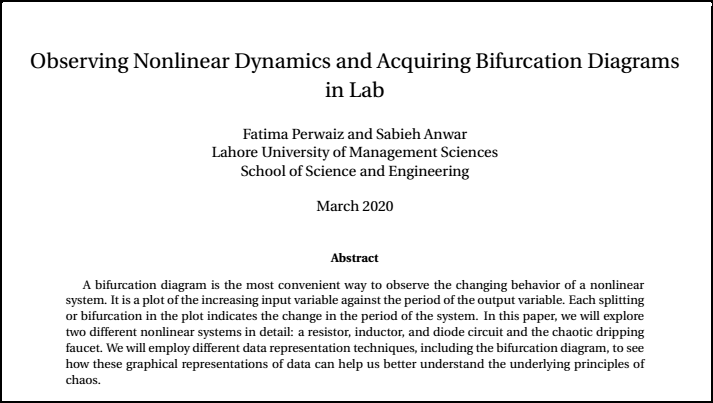

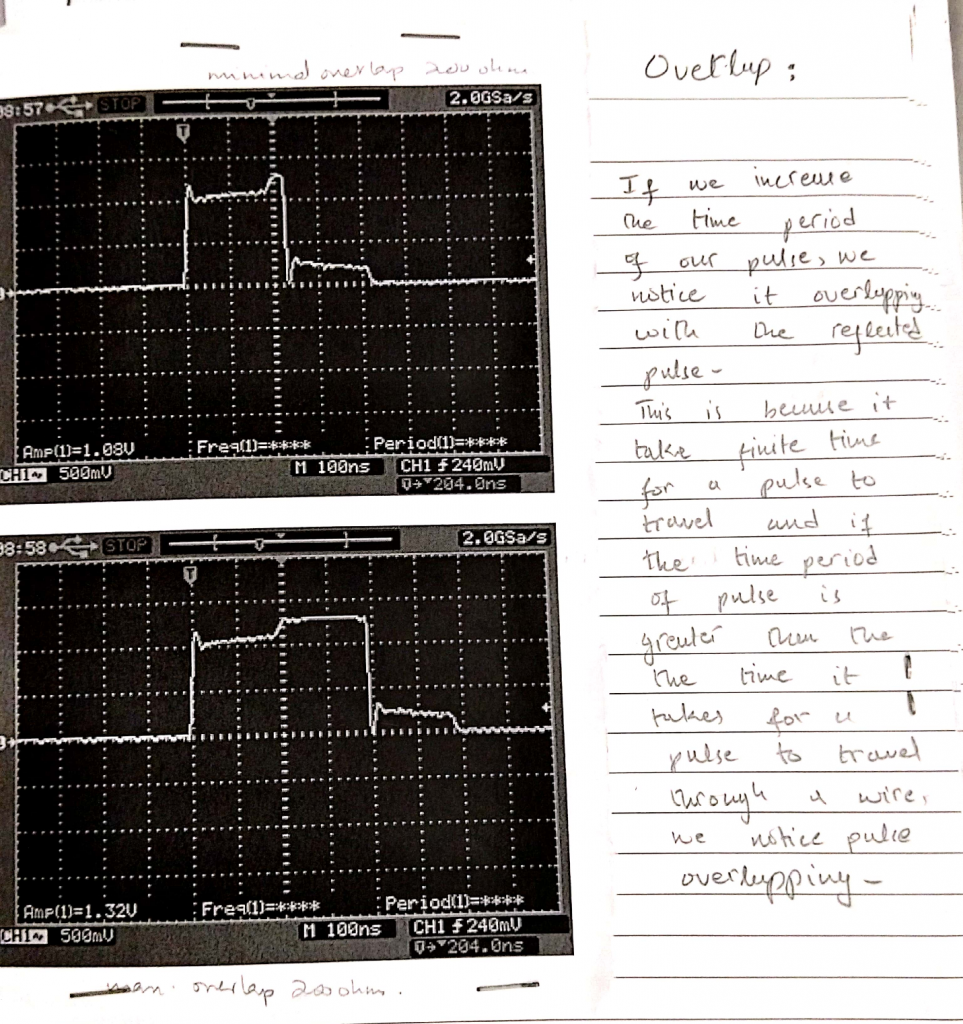

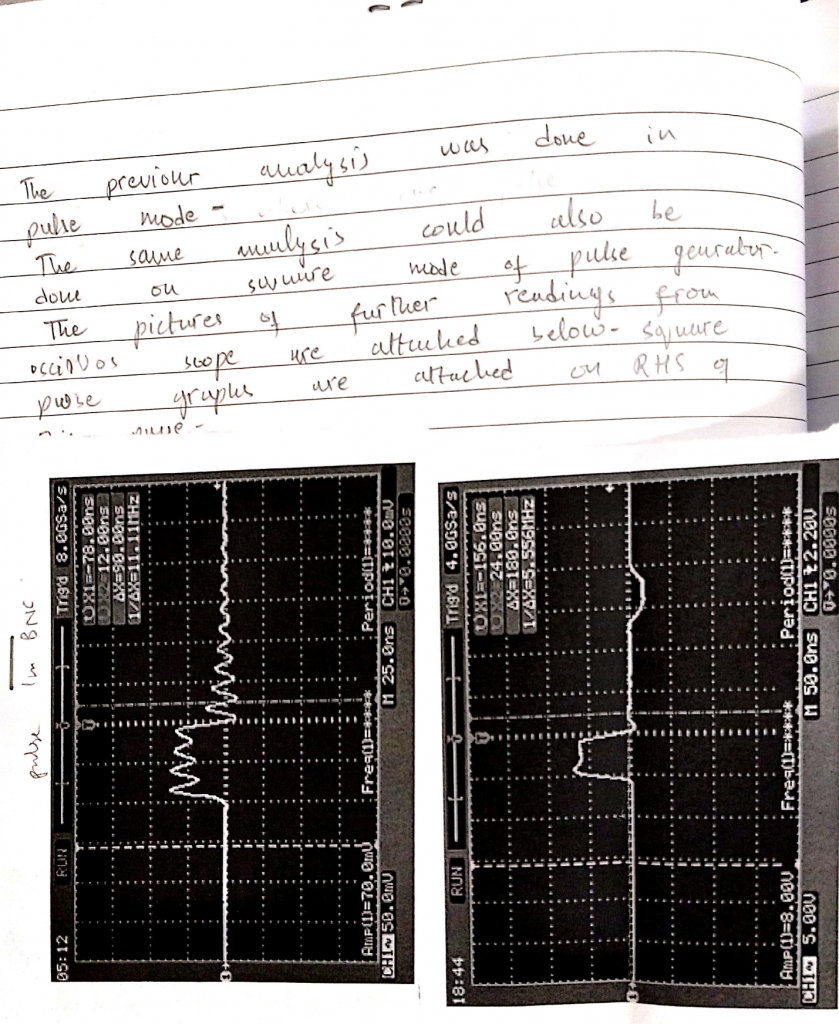

Many people believe that lab notebooks are only for putting down results. It is another misconception. Your lab diary should be a well-written account of all your activities regarding the experiment. It is a repertoire. It should contain the theory that you studied prior to the experiment, the set-up for the experiment, any changes that you have introduced in the set-up, the equipment you are using, along with their settings, snapshots of the plots obtained, data sets, any calculations performed, any inferences made, and more. Maintaining a lab notebook in this manner might seem gratuitous or trivial, but it is absolutely necessary for writing a comprehensive report.

Lab instructors love to see students’ notebooks that are adorned with sketches, illustrations, and even cartoons, if needed. They consider the notebook a visual representation of what goes in the experimentalist’s mind. The best notebook is the one that speaks for itself. A second person must be able to reproduce an experiment just by rendering notes from a notebook, without the need for any additional human support.

|

|

| Some snippets from a student’s notebook who was working on an experiment based on electrical signals propagating in a transmission line. | |

2. LaTeX’ing your report

LaTeX is the most common and convenient option available for technical writing in physics. It allows you to include mathematical notations, add graphs and figures, make tables for data, and optimize the overall layout of the report. You can either download a LaTeX compiler onto your system or use a free online service such as Overleaf. There are several templates available on the website for different types of technical writings, including lab reports. You can choose an appropriate template depending on your experiment and the data obtained.

What are the main components of an experimental lab report?

Generally, a report for a lab experiment comprises of a few essential sections that are common to all. However, depending on the type of experiment or the methodology used, there could be variations in the basic structure.

Title

Like any other formal document, the lab report should begin with a concise but insightful title for the experiment. Make sure your title best describes the experiment. Avoid using ambiguous or generic titles for the report. Following the title comes the names of those who performed the experiment. There could be a primary author and several co-authors. Other details that can be added include the name of the institute and the date.

Abstract

Those who have ever taken a writing course would know what a thesis statement is. It is a statement in the introductory paragraph of the essay which establishes the stance regarding the issue and briefly states the supporting arguments. The entire essay is nothing but an elucidation of the thesis statement. The abstract of a report is quite like it. In the abstract, you introduce the topic of the investigation, the method used for obtaining reliable results, and the results you aim to attain. Usually, an abstract is no more than a few lines.

For a detailed report, which can easily go over ten pages, you can allocate an entire page for the title and abstract. However, for a simpler experiment with a concise report, you can start the introduction right after the abstract.

Introduction

Since the abstract is relatively concise, and many readers who aren’t familiar with the field might not fully understand it, it is useful to begin with an elaborative introduction. Beginning with the information that you suspect readers would already know is considered a good start. Dwelling upon it, you should subsequently lead readers to your investigation and explain what you aim to obtain from the experiment. It would be correct to say that while the abstract addresses the experts of the field, the introduction aims to explain the experiments to all the scientists who have some basic understanding of the subject and are interested in expounding it further.

Theory

There are several types of experiments. Some of them aim to investigate a new phenomenon or employ a new technique to produce results, while others aim only to recreate previous results to understand the process of scientific inquiry. The theory in the report depends on in which category your experiment lies. If you are only reproducing an already done experiment, without any significant alterations in the method, then it is more likely that the theory is quite well-known. It is not necessary to rewrite it on several pages. You can discuss the details briefly and give references in the end for interested readers to delve deeper on their own. In these cases, students should avoid reproducing text and figures from the laboratory manuals.

If, on the other hand, you are stepping into the unknown territory and researching relatively newer ideas, you would need to study its theory more rigorously and include a detailed theory-section in the report. Even in this case, stay focused. Don’t forget the purview of your experiment and only include theoretical details that are relevant.

For example, if there are any subtopics that you think readers will enjoy exploring, briefly allude at them and add references for the readers to do their homework. You want your readers to be active engagers who are not spoon-fed everything. This technique is quite prevalent in formally published scientific papers that have passed through rigorous peer-review. As researchers can’t discuss the vast number of topics relevant to the research, they only introduce them with appropriate and up-to-date references.

Experiment

In this section, you need to explain the set-up for the experiment and the procedure used. At times, performing the experiment is the most time-consuming part of the entire process, but you do not necessarily need to describe all the technical details in the report. Again, it would be best to record them in your journal, but not in the report. If you are using complex equipment or an uncommon, homegrown device, it is recommended to explain its functionality in context with your experiment.

In the experiment section of the report, there is one crucial thing that several students fail to understand. A report is different from a manual for the experiment. While the manual is the complete how-to guide to perform the experiment, the report mainly emphasizes on analyzing results and deducing conclusions. Thus, don’t include step-by-step details of the procedure and the lists of apparatus and equipment used. Instead, briefly touch upon the method of the experiment in a paragraph or two. The apparatus you use must also be seamlessly integrated into these paragraphs. Students should avoid redundant explanations for each step in the process, unless necessary.

You can also choose to include photographs of your experimental set-up as key sub-assembly – a clever trick that adds value to your experiment.

Results

As it is the results of the experiment that ultimately determine the potency of the hypothesis, this section holds eminent significance. Undoubtedly, the validity of the results is what matters the most. But at the same time, the representation of results also plays an equally vital role in gaining recognition from the scientific community. For example, many experiments deal with large datasets and several graphs that need to be interpreted to obtain results. As an adept scientific inquirer, you should explain the data and graphs in simple words and relate it to the theory. However, sometimes, it is tough for readers to actually see your claims through the data coming. This is where the representation of results can make a significant difference. By making the datasets and graphs palatable to the reader, you can save everyone’s time and keep them engaged in your study.

There is a considerable variation on how results are represented in different reports, and they depend on the type of experiment. If your results are mostly numerical, it is better to display them in a table or a graph. A useful tip in this regard would be to look at your results and ask yourself, “would your report look more organized and results more comprehensible if you represent them in tabular form?” If so, tabulate them. Or “would a graph work better and what kind?”

Discussion

Discussion is certainly the most crucial part of the report. Here the results are interpreted, and the initial questions raised in the report are answered. For some students, it is also the most complicated part of the experiment. It is clearly the section that requires a nudge to our scientific intuition and ‘wisdom’ of physics. But binding the experiment with its true meaning and placing it in the bigger scheme of physics is of foremost importance. This should really be the most interesting part of the lab report. Unfortunately, many a time, it is found to be quite mechanical and boring as many students exhaust their patience when they have reached the final hit (or the deadline for submission is looming around the corner).

This usually happens when students only follow the guidelines of the experiment manual without having a proper understanding of the objectives and theory of the investigation. One would find it tough to comment on whether the goals of the experiment have been achieved if they don’t know them in the first place. Such students usually end up making facile deductions that make the report assailable. Thus, before performing the experiment, study its theory thoroughly to understand what is it all about. Sometimes it is nice to appreciate even the historical place of the experiment.

The upshot is that in the Discussion, you should interpret your results and comment on noise and uncertainties too. You can also discuss the limitations, if any, in your procedure that might have hindered the process. Lastly, you can talk about any additional factors that you didn’t count for during the experiment but could have influenced your results. If you were given a second chance, what different would you do?

Conclusion

Adding a conclusion to your report is not always essential. If you have any culminating remarks that you think could summarize the experiment, you can include a conclusion. Some students restate the abstract with more technical details, as readers are more likely to understand them now. This is also a useful strategy. Lastly, it is always useful to tell the readers what you could not achieve. This sheds light on what you have achieved. Clever part!

References

Many students mistakenly think that references are not mandatory for a full-fledged report. As discussed earlier, it is not convenient to discuss all the subtopics regarding the experiment in the report. But to ensure that readers are not lost in the jungle of the web to find relevant information, references are the key. For theory, in particular, cite the information that is taken from a book, journal, or any online platform. It is also essential to avoid plagiarism.

So far, we have seen how a lab report is normally arranged. We now discuss some essential ingredients. A lab report in physics comprises of four major constituents: text, mathematical content, tables, and figures. We will discuss each of them individually and provide you with tips and tricks to improve the outcome.

Text in the Report

In textual narratives, it is important to implement the technicalities of writing correctly. The following are some points where students are found to make mistakes.

- Many students begin their reports quite thoughtfully. They study and verify each detail before adding it to their report. But after a few paragraphs, this rigor begins to compromise. They add superfluous details that bring no value to their research. To avoid this, before introducing any new idea into your report, ask yourself if the information is really relevant. In any scientific inquiry, quality matters over quantity, and brevity is the soul wit.

- Simple yet convincing writing is not everyone’s forte. Many people associate convoluted and lengthy sentences with good writing. For a scientific report, it is not the case. It is always recommended to compose concise and meaningful sentences. If you are writing about a complex piece of information, it is advised to break it down into shorter, succinct, and clearer sentences.

- Many students struggle with the consistency of the tense in the report. If you are currently writing the report, that means you’ve performed the experiment in the past, and your supervisor will read it in the future. So, which is the best tense to choose?

Work was done and the observations made can be written in the past tense. For example, ‘On increasing the voltage, the temperature of the resistor increased’ Whereas, general truths such as ‘smoking increases the risk of cancer’ and atemporal facts such as ‘the paper represents the side effects of smoking’ can be written in the present tense. Lastly, if you want to discuss any prospects for the research, you can opt for the future tense. For example, ‘in the follow-up experiment, we will explore the effects of air quality.’ - For a more complicated sentence, you might have to use more than one tenses in the sentence. For example, ‘In 1905, Einstein postulated that the speed of light is ‘ [1]

- For any formal writing, including a report, it is ideal to write in the third person. Writing in first is considered informal, whereas writing in the second person for a report makes no sense. The second person (you, yours, etc.) is common in a manual or an instructional note, such as the one you’re reading.

- Emphasize on the verb of the clause as it adds strength to the sentence.

| Not preferred | Preferred |

| The increase in temperature produced a significant increase in the rate of reaction. | The increase in temperature increased the rate of reaction. |

| The results show a comparison between catalyst A and catalyst B. | The results compare catalyst A and catalyst B. |

| An analysis can be performed on both the specimens. | Both the specimens were analyzed. |

| No oscillations were observed in the pendulum. | The pendulum did not oscillate |

- Do not use ambiguous and evasive language. For example, a sentence like ‘it is believed that the concentration of reactants affects the rate of reaction’ is incompetent and vague. It is unclear whose beliefs we are talking about. Instead, it should be written as ‘chemists believe…’, ‘we believe…’, etc.

- The report should appear like a logically consistent and unified thematic journey through the experiment. It shouldn’t feel like a hop-on, hop-off route in a labyrinth.

- Be consistent in capitalization. Avoid excessive capitalization: “the cathode” instead of “the Cathode” should be preferred. Only the pioneers in the field have the liberty of using this stately language.

- Avoid starting sentences with “and”, “now”, “also”, “then”, with symbols and numerals (1,2,565, -3, E, Vi), or any abbreviations.

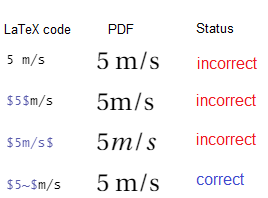

- In LaTeX, mathematical expressions or equations can be written in math mode by writing between the dollar signs — $…$. For example, “The voltage is increased to $4$ volts”.

- Be careful while writing units and symbols in text.

Mathematical content

For a report that includes derivations or calculations, the mathematical part of the report needs to be impeccable. Careless mistakes in calculation or improper structure of the derivation can make people question the validity of the rest of the paper. The following are some tricks and techniques to avoid reckless errors in the mathematical components.

- While it is encouraged to perform ALL the calculations in your lab notebook, it is not wise to include them all in the report. Scientists or researchers who would later review your paper need not be burdened with trivial calculations. Thus, to save time, it is suggested not to include all the steps of the calculation in the final report.

- Add appendix(es) at the end of your report if there are indeed lengthy but essential calculations to be included.

- LaTeX allows you to number every equation in the report to be referred to later. However, numbering all equations can clutter your report. To keep things simple and straightforward, number only the important equations you might be using again in the report.

- Treat equations like sentences. Showing a derivation or calculation in a report is not about merely stating numbers. Instead, each line of calculation should be presented as a sentence with proper punctuation.

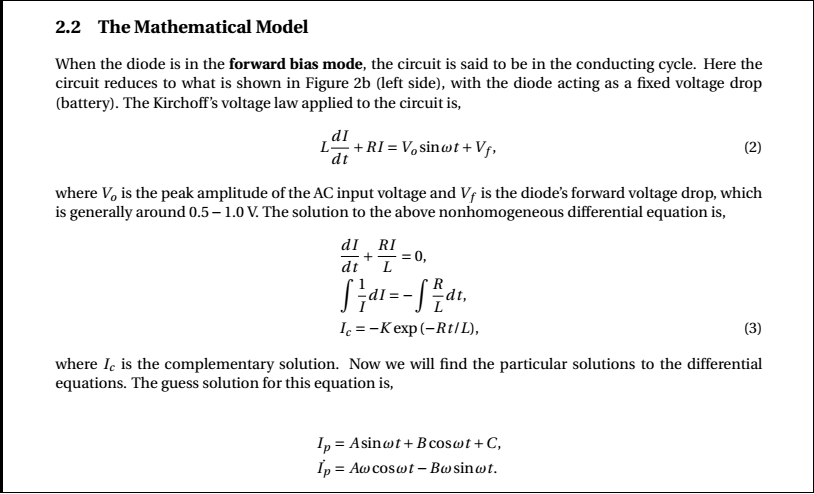

The mathematical model for an experiment is shown to explain how to treat equations like sentences. Since equation 2 in the figure ends with a coma, the next line doesn’t begin with a capital letter. Each equation in the report should have a punctuation mark like any regular sentence.

Figures and Plots in the Report

When it comes to an experimental report, pictures can speak louder than words. Diagrams and plots used to describe the set-up or the results of the experiment can make or break your research. So, here are some tips to make sure you are doing the right job with figures. Interested students can also refer to one of the author’s (Dr Sabieh) video recorded lectures on effective graphing techniques. [2]

- Any plots included in the report should be fully labelled. All its axis should be marked with the correct quantity and units. And the units should be in LaTeX math mode.

- Before adding any figure to the report, make sure the markings of the axis are legible and complement the size of the plot. Readjust the plot if required.

- Check the scaling of the figure to make sure that the regions of the plot that show any salient features, such as kinks, transitions, doubling, etc. are clearly visible.

- Remove unwanted data or labels on the figure such as legend boxes showing “data 6″, “data 7”. The data identifiers are good to keep in your lab notebook but are clumsy for a lab report.

- When a plot is saved from any software such as MATLAB or LabVIEW, make sure it is saved in the PDF format or as a vector graphic. PDF images do not lose their quality when zoomed in or zoomed out. Don’t convert the images to bitmaps. The image resolution is really important because you might want to alter and reuse the image later.

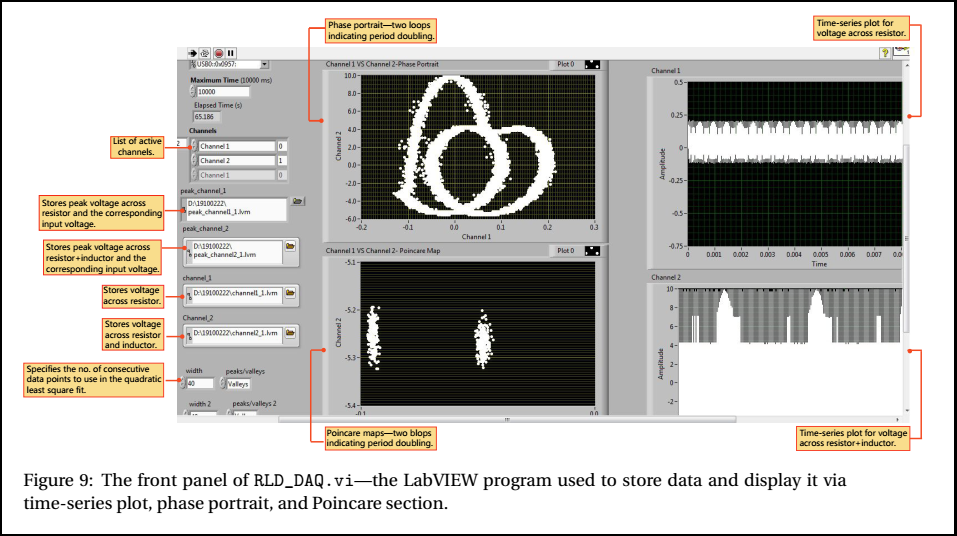

- If you are adding a screenshot of a software interface used in the experiment, make sure to label it correctly for the reader’s ease.

A fully labelled screenshot of an interface used in an experiment. Such a figure can be used in the report to show how the software worked.

All the plots used in the report should be original. Avoid reusing figures from the manual. If you are using figures from a book or a journal, cite them properly.

- Every figure included in the report should have a brief caption above or below it to describe what is being displayed.

- In LaTeX, all the figures used in the report can be referred to in the text. Make sure that there is a sufficient level of cross-referencing and linking of graphs to the text. Also, figures should appear in the same order as they are referred to in the main body of the report.

- If helpful, include a photograph of the real set-up of the experiment. While taking a picture of the set-up, make sure its background is clear, and only the relevant equipment and tools are in the frame.

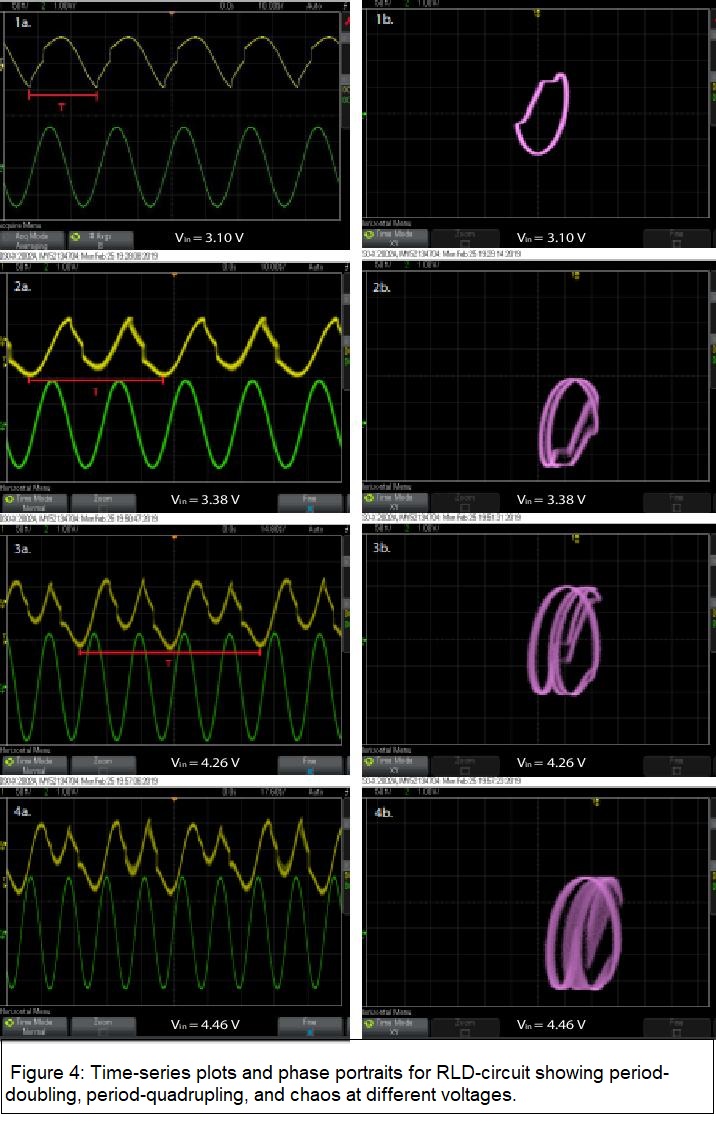

- If your experiment is about observing changes in a phenomenon through graphical plots, make sure to arrange all the plots in one figure as subplots before adding them to the report. It is inconvenient for readers to look at individual plots on different pages to compare them to one another.

Four different time-series plot and phase portraits have been compiled into one to illustrate the effect of increasing voltage on the period of the waveform.

Tabular Data

Several experiments have myriads of datasets that researchers find difficult to state in words and readers tiresome to comprehend. The issue can be resolved by using well-organized and properly labelled tables to display results effectively. However, it recommended using tables where plots may not work. The following are some tips to help you with the tables in your report.

- All the tables in the report should have suitable headings of the quantity being displayed along with its units in LaTeX math mode.

- LaTeX allows the tables in the report to be referred to in the text. Make sure that there is a sufficient level of cross-referencing and linking of tables to the text.

- Every table included in the report should have a brief caption above or below it to describe what is being displayed.

Bonus Tips

- Most authors write the abstract at the very end. This way one can write a more discerning and thorough abstract that encompasses the essence of the experiment as one gets a better picture of what the experiment is after all, all about!

- Before performing the experiment, write down in your journal the objective(s) for the experiment – the exact thing that the investigation aims to achieve. Don’t begin the experiment unless you are clear with the goal. Ask your supervisor or seniors until you get a satisfactory answer. This not only gives you a sense of direction but also helps you interpret and gauge your results through a critical lens.

- Don’t try to impress your professors with tons of pages dedicated to the theory, especially for the topics that aren’t even related to the experiment. Instead, only include content that you found useful to understand and prepare for the experiment.

- Don’t underestimate the importance of art in your lab reports. It not only makes everything easy but also breaks the visual monotony of a long spattering of text. Sketches and vivid illustrative techniques enhance the attractiveness of your report and make it lively and simply comprehensible.

- You can use a free online citation site such as Easybib to get a citation in the correct format or do it manually on LaTeX.

Final words

Laboratory instructors and supervisors are not looking for an uninteresting account of the procedure regurgitated from the manual. What they want is a concise description of the procedure interwoven with insights, discussions, suggestions, and interpretations. Your professors are human, and they are reading several reports, often on the same or similar experiments. Try to stand out and make it a worthwhile experience for them.

Lastly, LaTeX is a versatile platform that provides students with flexible options to modify their reports. All that one needs to do is search for their concerns online and find a solution. Always remember, there are thousands of students who have compiled lab reports before you and have faced issues like yours. Use their tips and advices available on different forums to produce an insightful and well-articulated piece of writing.

We hope this was helpful.

Happy Lab Reporting!

PS: Here’s a sample report marked by Dr Sabieh Anwar.

Work Cite

[1] https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/effective-writing-13815989/

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BAwfUsSq5lg&feature=emb_title